- Home

- Jennifer Haigh

The Condition

The Condition Read online

The Condition

A Novel

Jennifer Haigh

Epigraph

In nature, all is useful, all is beautiful.

—ralph waldo emerson, “Art”

To regret deeply is to live afresh.

—henry david thoreau, Journals

Contents

Epigraph

1976

The Captain’s House

1997

The Condition

Chapter 1

Snow was falling fast in Cambridge, small dry flakes, oblique…

Chapter 2

Three days before Christmas, Scott McKotch saw the billboard.

Chapter 3

Tom and Richard served sushi for dinner. The delicate bundles…

1998

The Cure

Chapter 4

Gwen packed her gear carefully. The duffel bag was narrow…

Chapter 5

Halfway through a wet April, Massachusetts went to war.

Chapter 6

What he’d lacked his whole life—Scott understood this now—was a…

Chapter 7

The sun rises over St. Raphael. Gwen wakes first, roused…

Chapter 8

Scott had become an early riser. His whole life he…

Chapter 9

For most of her life, Paulette had loved Sundays. As…

Chapter 10

Cape Cod is the bared and bended arm of Massachusetts.

Prognosis

Author’s Note

About the Author

Other Books by Jennifer Haigh

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

1976

the captain’s house

Summer comes late to Massachusetts. The gray spring is frosty, unhurried: wet snow on the early plantings, a cold lesson for optimistic gardeners, for those who have not learned. Chimneys smoke until Memorial Day. Then, all at once, the ceiling lifts. The sun fires, scorching the muddy ground.

At Cape Cod the rhythm is eternal, unchanging. Icy tides smash the beaches. Then cold ones. Then cool. The bay lies warming in the long days. Blue-lipped children brave the surf.

They opened the house the third week in June, the summer of the bicentennial, and of Paulette’s thirty-fifth birthday. She drove from Concord to the train station in Boston, where her sister was waiting, then happily surrendered the wheel. Martine was better in traffic. She’d been better in school, on the tennis court; for two years straight she’d been the top-ranked singles player at Wellesley. Now, at thirty-eight, Martine was a career girl, still a curiosity in those days, at least in her family. She worked for an advertising agency on Madison Avenue—doing what, precisely, Paulette was not certain. Her sister lived alone in New York City, a prospect she found terrifying. But Martine had always been fearless.

The station wagon was packed with Paulette’s children and their belongings. Billy and Gwen, fourteen and twelve, rode in the backseat, a pile of beach towels between them. Scotty, nine and so excited about going to the Cape that he was nearly insufferable, had been banished to the rear.

“God, would you look at this?” Martine downshifted, shielding her eyes from the sun. The traffic had slowed to a crawl. The big American engines idled loudly, the stagnant air rich with fumes. The Sagamore Bridge was still half a mile away. “It gets worse every year. Too many goddamned cars.”

A giggle from the backseat, Gwen probably. Paulette frowned. She disapproved of cursing, especially by women, especially in front of children.

“And how was the birthday?” Martine asked. “I can’t believe la petite Paulette is thirty-five. Did you do anything special?”

Her tone was casual; she may not have known it was a tender subject. Like no birthday before, this one had unsettled Paulette. The number seemed somehow significant. She’d been married fifteen years, but only now did she feel like a matron.

“Frank took me into town. We had a lovely dinner.” She didn’t mention that he’d also reserved a room at the Ritz, a presumptuous gesture that irritated her. Like all Frank’s presents, it was a gift less for her than for himself.

“Will he grace us with his presence this year?”

Paulette ignored the facetious tone. “Next weekend, maybe, if he can get away. If not, then definitely for the Fourth.”

“He’s teaching this summer?”

“No,” Paulette said carefully. “He’s in the lab.” She always felt defensive discussing Frank’s work with Martine, who refused to understand that he wasn’t only a teacher but also a scientist. (Molecular developmental biology, Paulette said when anyone asked what he studied. This usually discouraged further questions.) Frank’s lab worked year-round, seven days a week. Last summer, busy writing a grant proposal, he hadn’t come to the Cape at all. Martine seemed to take this as a personal slight, though she’d never seemed to enjoy his company. He’s an academic, she’d said testily. He gets the summers off. Isn’t that the whole point? It was clear from the way she pronounced the word what she thought of academics. Martine saw in Frank the same flaws Paulette did: his obsession with his work, his smug delight in his own intellect. She simply didn’t forgive him, as Paulette—as women generally—always had. Frank had maintained for years that Martine hated him, a claim Paulette dismissed. Don’t be silly. She’s very fond of you. (Why tell such a lie? Because Martine was family, and she ought to be fond of Frank. Paulette had firm ideas, back then, of how things ought to be. )

In Truro the air was cooler. Finally the traffic thinned. Martine turned off the highway and onto the No Name Road, a narrow lane that had only recently been paved. Their father had taught the girls, as children, to recite the famous line from Thoreau: Cape Cod is the bared and bended arm of Massachusetts. The shoulder is at Buzzard’s Bay; the elbow at Cape Mallebarre; the wrist at Truro; and the sandy fist at Provincetown.

Remembering this, Paulette felt a stab of tenderness for her father. Everett Drew had made his living as a patent attorney, and viewed ideas as property of the most precious kind. In his mind Thoreau was the property of New England, of Concord, Massachusetts, perhaps even particularly of the Drews.

“Is Daddy feeling better?” Paulette asked. “I’ve been worried about his back.” Martine had just returned from Florida, where their parents had retired and Ev was now recovering from surgery. Paulette visited when she could, but this was no substitute for Sunday dinners at her parents’ house, the gentle rhythm of family life, broken now, gone forever.

“He misses you,” said Martine. “But he made do with me.”

Paulette blinked. She was often blindsided by how acerbic her sister could be, how in the middle of a pleasant conversation Martine could deliver a zinger that stopped her cold: the backhanded compliment, the ripe apple with the razor inside. When they were children she’d often crept up behind Paulette and pulled her hair for no reason. It wasn’t her adult life, alone in a big city, that had made Martine prickly. She had always been that way.

They turned off the No Name Road onto a rutted path. It being June, the lane was rugged, two deep tire tracks grown in between with grass. By the end of summer, it would be worn smooth. The Captain’s House was set squarely at the end of it, three rambling stories covered in shingle. A deep porch wrapped around three sides.

As she had every summer of her life, Paulette sprang out of the car first, forgetting for a moment her children in the backseat, Scotty whiny and fidgeting in the rear. For a split second she was a girl again, taking inventory, checking that all was as she’d left it the year before. Each member of the family performed some version of this ritual. Her brother Roy rushed first to the boathouse, Martine to the sandy beach.

But it was the cotta

ge itself that called to Paulette, the familiar stairs and hallways, the odd corners and closets and built-in cupboards where she’d hidden as a child—the tiniest of the Drew cousins, a little Houdini—in games of hide-and-seek. The Captain’s House, the family called it, in memory of Clarence Hubbard Drew, Paulette’s great-great-grandfather, a sailor and whaler. Clarence had hired a distinguished architect, a distant cousin of Ralph Waldo Emerson. The house had the graceful lines of the shingle style; it was built for comfort rather than grandeur. A house with wide doors and windows, a house meant to be flung open. On summer nights a cross breeze whipped through the first floor, a cool tunnel of ocean-smelling air.

Paulette stood a moment staring at the facade, the house’s only architectural flourish: three diamond-shaped windows placed just above the front door. The windows were set in staggered fashion, rising on the diagonal like stairs, a fact Paulette, as a child, had found significant. She was the lowest window, Roy the highest. The middle window was Martine.

She noticed, then, a car parked in the sandy driveway that curved behind the house. Her brother’s family had already arrived.

“Will you look at that?” said Martine, coming up behind her. “Anne has a new Mercedes.”

Paulette, herself, would not have noticed. In such matters she deferred to her husband, who was partial to Saabs and Volvos.

Martine smirked. “Roy has come up in the world.”

“Martine, hush.” Paulette refused to let her sister spoil this moment, the exhilarating first minutes of summer, the joyful return.

They unloaded the car: brown paper bags from the grocery store in Orleans, the oblong case that held Gwen’s telescope. Tied to the roof were suitcases and Billy’s new ten-speed, an early birthday present. Martine stood on her toes to unfasten them.

“I’ll do it,” said Billy, untying the ropes easily, his fingers thick as a man’s. He had sailed since he was a toddler and was a specialist at complicated knots. Not quite fourteen, he towered over his mother. He had been a beautiful child, and would be an exceptionally handsome man; but that summer Paulette found him difficult to look at. His new maturity was everywhere: his broad shoulders, his coarsening voice, the blond peach fuzz on his upper lip. Normal, natural, necessary changes—yet somehow shocking, embarrassing to them both.

They followed the gravel path, loaded down with groceries, and nudged open the screen door. A familiar scent greeted them, a smell Paulette’s memory labeled Summer. It was the smell of her own childhood, complex and irreducible, though she could identify a few components: sea air; Murphy’s oil soap; cedar closets that had stood closed the long winter, the aged wood macerating in its own resins, waiting for the family to return.

Paulette put down the groceries in the airless kitchen, wondering why her sister-in-law hadn’t thought to open the windows. Billy carried the bags up the creaking stairs. The house had nine bedrooms, a few so small that only a child could sleep there without suffering claustrophobia. The third-floor rooms, stifling in summertime, were rarely used. The same was true of the tiny alcove off the kitchen, which had once been the cook’s quarters. Since her marriage Paulette had slept in a sunny front bedroom—Fanny’s Room, according to the homemade wooden placard hanging on the door. Fanny Porter had been a school chum of Paulette’s grandmother; she’d been dead thirty years or more, but thanks to a long-ago Drew cousin, who’d made the signs as a rainy-day project at the behest of some governess, the room would forever be known as Fanny’s.

The sleeping arrangements at the house were the same each year. Roy and Anne took the Captain’s Quarters at the rear of the house, the biggest room, with the best view. Frank, if he came, would grouse about this, but Paulette didn’t mind. Someone had to sleep in the Captain’s Quarters, to take her father’s place at the dinner table. That it was Roy, the eldest son, seemed correct, the natural order of things. Correct too that Gwen shared prime accommodations, with Roy’s two daughters, on the sleeping porch, where Martine and Paulette and their Drew cousins had slept as girls. The porch was screened on three sides; even on the hottest nights, ocean breezes swept through. Across the hall was the Lilac Room, named for its sprigged wallpaper; and Martine’s favorite, the Whistling Room, whose old windows hummed like a teakettle when the wind came in from the west. Billy and Scotty took the wood-paneled downstairs bedroom—the Bunk House—where Roy and the boy cousins had once slept. It was this sameness that Paulette treasured, the summer ritual unchanging, the illusion of permanence.

THAT AFTERNOON they packed a picnic basket and piled into the car. Their own bit of coastline—the family called it Mamie’s Beach—had been the natural choice when the children were small. Now that the boys had discovered body-surfing, the rougher waters of the National Seashore held greater appeal. For this brief trip Paulette took the wheel, with a confidence she never felt in Boston. She loved driving the Cape roads, familiar, gently winding; she could have driven them in her sleep. Scotty claimed the passenger seat after a tussle with his brother. (“Billy, darling, just let him have it, will you?” she’d pleaded.) After sitting in the car all morning, her youngest was wild as a cat. In this state Paulette found him ungovernable and rather frightening. Her only hope was to turn him loose outdoors, where he could run and roar the whole afternoon.

She sat on a blanket in the shade of an umbrella, My Ántonia lying open in her lap. She’d brought Lord of the Flies for Billy, who would read his daily chapter without complaint, and Little Women for Gwen, who would not. Paulette believed firmly in summer reading, and because she’d loved the Alcott books as a girl, she couldn’t fathom why Gwen did not. Seeing Orchard House had been the greatest thrill of Paulette’s twelve-year-old life. “That’s where Louisa grew up, right here in Concord,” she’d told her daughter. This proved to be insufficient enticement. After a week of cajoling, Gwen still hadn’t opened the book.

Paulette shifted slightly, moving nearer the umbrella. Its positioning had been the subject of much discussion. Her sister-in-law, Anne, coated in baby oil, wanted as much sun as possible; Paulette needed complete shade. She’d been cautioned by visiting her parents in Palm Beach, a town populated by leathery retirees who lived their lives poolside, their bodies lined in places she’d never imagined could wrinkle.

Martine stood back from the discussion, laughing at them both. “You make quite a picture,” she said. Paulette wore a large straw hat and, over her swimsuit, striped beach pajamas, their wide legs flapping like flags in the wind. Anne wore a white bikini more suited to a teenager. The bikini was made of triangles. Two inverted ones made up the bottom. Two smaller ones, attached by string, formed the top.

Paulette had known Anne most of her life. Roy had met her his final year at Harvard, when Paulette was fourteen, and she had fallen in love with Anne too. They were as close as sisters—closer, certainly, than Paulette and Martine. Paulette admired her sister, but couldn’t confide in her. Martine seemed to find the world so easy. She had no patience for someone who did not.

Anne lit a cigarette. After giving birth to her second daughter, she’d taken up smoking to regain her figure. Charlotte was twelve now, and Anne, so thin her ribs showed, still smoked.

They watched as Martine joined the boys in the surf. In the ocean she was a daredevil. Paulette got nervous just watching her. Martine waiting for her moment, her slick head bobbing; Martine diving fearlessly into the waves.

“You can relax now,” Anne said, chuckling. “Auntie Lifeguard is on duty.”

“That’s the problem. She’ll get them all killed.” Paulette shifted slightly, to avoid the streaming smoke. “When is Roy coming?”

“Friday morning. He’s dying to put the boat in the water.” Anne rolled onto her stomach, then untied her bikini top. “Can you grease my back?”

Paulette took the baby oil Anne offered and squirted it into her hands. Anne’s skin felt hot and papery, dry to the touch.

“I don’t know if Frank will make it this year,” said Paulette. I don’t know i

f I want him to, she nearly added. At home they coexisted peacefully, more or less, though Frank spent so much time at the lab that they rarely saw each other. At the Cape they’d have to spend long days together. What will we talk about all day? she wondered. What on earth will we do?

She knew what Frank would want to do. His sexual demands overwhelmed her. If he’d asked less often, she might have felt bad about refusing; but if Frank had his way, they would make love every night. After fifteen years of marriage, it seemed excessive. Paulette sometimes wondered whether other couples did it so often, but she had no one to ask. Anne didn’t shrink from personal questions, but she was Roy’s wife. Certain things, Paulette truly didn’t want to know.

Married sex: the familiar circuit of words and caresses and sensations, shuffled perhaps, but in the end always the same. The repetition wore on her. Each night when Frank reached for her she felt a hot flicker of irritation, then tamped it down. She willed herself to welcome him, to forget every hurt and disappointment, to hold herself open to all he was and wasn’t. The effort exhausted her.

Years later she would remember those marital nights with tenderness: for the brave young man Frank had been, and for her young self, the wounded and stubborn girl. She’d had a certain idea about lovemaking, gleaned from Hollywood or God knew where, that a man’s desire should be specific to her, triggered by her unique face or voice or—better—some intangible quality of her spirit; and that of all the women in the world, only she should be able to arouse him. And there lay the problem. Frank’s passion, persistent and inexhaustible, seemed to have little to do with her. He came home from work bursting with it, though they hadn’t seen or spoken to each other in many hours. “I’ve been thinking about this all day,” he sometimes whispered as he moved inside her.

The Condition

The Condition Zenith Man

Zenith Man Baker Towers

Baker Towers News From Heaven

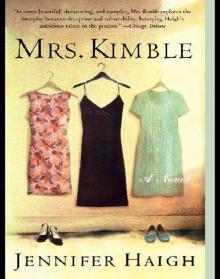

News From Heaven Mrs. Kimble

Mrs. Kimble