- Home

- Jennifer Haigh

Baker Towers

Baker Towers Read online

Baker Towers

JENNIFER HAIGH

Dedication

In memory of my father,

Jay Wasilko

Epigraph

If grief could burn out

Like a sunken coal,

The heart would rest quiet.

PHILIP LARKIN

All the brothers were valiant, and all the sisters virtuous.

INSCRIPTION ON A TOMB

IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY

The family is the country of the heart.

GIUSEPPE MAZZINI,

THE DUTIES OF MAN

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

One

Softly the snow falls. In the blue morning light a…

Two

Years later, when her time in Washington had receded from…

Three

They came back in the summer, weighed down with treasures.

Four

The town grew.

Five

The Bakerton Volunteer Fire Company sat at the corner of…

Six

Fall froze into winter. The Monday after Thanksgiving, men donned…

Seven

Just before Christmastime, Gene Stusick presented a new contract to…

Eight

Forever after, when the story is told—in newspapers and…

Nine

Everything froze.

Ten

The town wore away like a bar of soap. Each…

Excerpt from Heaven

News from the Heaven

Beast and Bird

Back Ad

Praise

Acknowledgments

About the Author

E-book Extra

An Interview with Jennifer Haigh

E-book Extra

Reading Group Guide

Also by Jennifer Haigh

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

One

Softly the snow falls. In the blue morning light a train winds through the hills. The engine pulls a passenger car, brightly lit. Then a dozen blind coal cars, rumbling dark.

Six mornings a week the train runs westward from Altoona to Pittsburgh, a distance of a hundred miles. The route is indirect, tortuous; the earth is buckled, swollen with what lies beneath. Here and there, the lights of a town: rows of company houses, narrow and square; a main street of commercial buildings, quickly and cheaply built. Brakes screech; the train huffs to a stop. Cars are added. In the passenger compartment, a soldier on furlough clasps his duffel bag, shivers and waits. The whistle blows. Wheezing, the engine leaves the station, slowed by the extra tons of coal.

The train crosses an iron bridge, the black water of the Susquehanna. Lights cluster in the next valley. The town, Bakerton, is already awake. Coal cars thunder down the mountain. The valley is filled with sound.

The valley is deep and sharply featured. Church steeples and mine tipples grow inside it like crystals. At bottom is the town’s most famous landmark, known locally as the Towers, two looming piles of mine waste. They are forty feet high and growing, graceful slopes of loose coal and sulfurous dirt. The Towers give off an odor like struck matches. On windy days they glow soft orange, like the embers of a campfire. Scrap coal, spontaneously combusting; a million bits of coal bursting into flame.

Bakerton is Saxon County’s boomtown. Like the Towers, it is alive with coal. A life that started in the 1880s, when two English brothers, Chester and Elias Baker, broke ground on Baker One. Attracted by hand-bills, immigrants came: English and Irish, then Italians and Hungarians; then Poles and Slovaks and Ukrainians and Croats, the “Slavish,” as they were collectively known. With each new wave the town shifted to make room. Another church was constructed. A new cluster of company houses appeared at the edge of town. The work—mine work—was backbreaking, dangerous and bleak; but at Baker Brothers the union was tolerated. By the standards of the time the pay was generous, the housing affordable and clean.

The mines were not named for Bakerton; Bakerton was named for the mines. This is an important distinction. It explains the order of things.

Chester Baker was the town’s first mayor. During his term Bakerton acquired the first streetcar line in the county, the first public water supply. Its electric street lamps were purchased from Baker’s own pocket. Figure the cost of maintaining them for fifty years, he wrote to the town bosses, and I will pay you the sum in advance. After twenty years Baker ceded his office, but the bosses continued to meet at his house, a rambling yellow-brick mansion on Indian Hill. A hospital was built, the construction crew paid from a fund Baker had established. He wouldn’t let the building be named for him. At his direction, it was called Miners’ Hospital.

The hospital was constructed in brick; so were the stores, the dress factory, the churches, the grammar school. After the Commercial Hotel burned to the ground in 1909, an ordinance was passed, urging merchants to “make every effort to fabricate their establishments of brick.” To a traveler arriving on the morning train—by now an expert on Pennsylvania coal towns—the hat shop and dry-goods store, the pharmacy and mercantile, seem built to last. Their brick facades suggest order, prosperity, permanence.

ON THE SEVENTEENTH of January 1944, a motorcar idled at the railroad crossing, waiting for the train to pass. In the passenger seat was an elderly undertaker of Sicilian descent, named Antonio Bernardi. At the wheel was his great-nephew Gennaro, a handsome, curly-haired youth known in the pool halls as Jerry. Between them sat a blond-haired boy of eight. The car, a black Packard, had been waxed that morning. The old man peered anxiously through the windshield, at the snowflakes melting on the hood.

“These Slavish,” he said, as if only a Pole would drop dead in the middle of winter and expect to be buried in a snowstorm.

The train passed, whistle blowing. The Packard crossed the tracks and climbed a steep road lined with company houses, a part of town known as Polish Hill. The road was loose and rocky; the coarse stones, called red dog, came from bony piles on the outskirts of town. Black smoke rose from the chimneys; in the backyards were outhouses, coal heaps, clotheslines stretched between posts. Here and there, miners’ overalls hung out to dry, frozen stiff in the January wind.

“These Slavish,” Bernardi said again. “They live like animali.” At one time, his own brothers had lived in company houses, but the family had improved itself. His nephews owned property, houses filled with modern comforts: telephones and flush toilets, gas stoves and carpeted floors.

“Papa,” said Jerry, glancing at the boy; but the child seemed not to hear. He stared out the window wide-eyed, having never ridden in a car before. His name was Sandy Novak; he’d come knocking at Bernardi’s back door an hour before—breathless, his nose dripping. His mother had sent him running all the way from Polish Hill, to tell Bernardi to come and get his father.

The car climbed the slope, engine racing. Briefly the tires slid on the ice. At the top of the hill Jerry braked.

“Well?” said the old man to the boy. “Where do you live?”

“Back there,” said Sandy Novak. “We passed it.”

Bernardi exhaled loudly. “Cristo. Now we got to turn around.”

Jerry turned the car in the middle of the road.

“Pay attention this time,” Bernardi told the boy. “We don’t got all day.” In fact he’d buried nobody that week, but he believed in staying available. Past opportunities—fires, rockfalls, the number five collapse—had arisen without warning. Somewhere in Bakerton a miner was dying. Only Bernardi could deliver him to God.

The Bernardis handled funerals at the five Catholic churches in town. A man named Hiram Stoner had a similar arrangement with the Protestants. When Bern

ardi’s black Packard was spotted, the town knew a Catholic had died; Stoner’s Ford meant a dead Episcopalian, Lutheran or Methodist. For years Bernardi had transported his customers in a wagon pulled by two horses. During the flu of ’18 he’d moved three bodies at a time. Recently, conceding to modernity, he’d bought the Packard; now, when a Catholic died, a Bernardi nephew would be called upon to drive. Jerry was the last remaining; the others had been sent to England and northern Africa. The old man worried that Jerry, too, would be drafted. Then he’d have no one left to drive the hearse.

“There it is,” the boy said, pointing. “That’s my house.”

Jerry slowed. The house was mean and narrow like the others, but a front porch had been added, painted green and white. One window, draped with lace curtains, held a porcelain statue of the Madonna. In the other window hung a single blue star.

“Who’s the soldier?” said Jerry.

“My brother Georgie,” said Sandy, then added what his father always said. “He’s in the South Pacific.”

They climbed the porch stairs, stamping snow from their shoes. A woman opened the door. Her dark hair was loose, her mouth full. A baby slept against her shoulder. She was beautiful, but not young—at least forty, if Bernardi had to guess. He was like a timberman who could guess the age of a tree before counting the rings inside. He had rarely been wrong.

She let them inside. Her eyelids were puffy, her eyes rimmed with red. She inhaled sharply, a moist, slurry sound.

Bernardi offered his hand. He’d expected the usual Slavish type: pale and round-faced, a long braid wrapped around her head so that she resembled a fancy pastry. This one was dark-eyed, olive-skinned. He glanced down at her bare feet. Italian, he realized with a shock. His mother and sisters had never worn shoes in the house.

“My dear lady,” he said. “My condolences for your loss.”

“Come in.” She had an ample figure, heavy in the bosom and hip. The type Bernardi—an old bachelor, a window-shopper who’d looked but had never bought—had always liked.

She led them through a tidy parlor—polished pine floor, a braided rug at the center. A delicious aroma came from the kitchen. Not the usual Slavish smell, the sour stink of cooked cabbage.

“This way,” said the widow. “He’s in the cellar.”

They descended a narrow staircase—the widow first, then Jerry and Bernardi. The dank basement smelled of soap, onions and coal. The widow switched on the light, a single bare bulb in the ceiling. A man lay on the cement floor—fair-haired, with a handlebar mustache. A silver medal on a chain around his neck: Saint Anne, protectress of miners. His hair was wet, his eyes already closed.

“He just come home from the mines,” said the widow, her voice breaking. “He was washing up. I wonder how come he take so long.”

Bernardi knelt on the cold floor. The man was tall and broad-shouldered. His shirt was damp; the color had already left his face. Bernardi touched his throat, feeling for a pulse.

“It’s no point,” said the woman. “The priest already come.”

Bernardi grasped the man’s legs, leaving Jerry the heavier top half. Together they hefted the body up the stairs. Bernardi was sixty-four that spring, but his work had kept him strong. He guessed the man weighed two hundred pounds, heavy even for a Slavish.

They carried the body out the front door and laid it in the rear of the car. The boy watched from the porch. A moment later the widow appeared, still holding the baby. She had put on shoes. She handed Bernardi a dark suit on a hanger.

“He wore it when we got married,” she said. “I hope it still fits.”

Bernardi took the suit. “We’ll bring him back tonight. How about you get a couple neighbors to help us? He’ll be heavier with the casket.”

The widow nodded. In her arms the baby stirred. Bernardi smiled stiffly. He found infants tedious; he preferred them silent and unconscious, like this one. “A little angel,” he said. “What’s her name?”

“Lucy.” The widow stared over his shoulder at the car. “Dio mio. I can’t believe it.”

“Iddio la benedica.”

They stood there a moment, their heads bowed. Gently Bernardi patted her shoulder. He was an old man; by his own count he’d buried more than a thousand bodies; he had glimpsed the darkest truths, the final secrets. Still, life held surprises. Here was a thing he had never witnessed, an Italian wife on Polish Hill.

THAT MORNING, the feast of Saint Anthony, Rose Novak had gone to church. For years the daily mass had been poorly attended, but now the churches were crowded with women. The choir, heavy on sopranos, had doubled in size. Wives stood in line to light a candle; mothers knelt at the communion rail in silent prayer. Since her son Georgie was drafted Rose had scarcely missed a mass. Each morning her eldest daughter, Dorothy, cooked the family breakfast, minded the baby, and woke Sandy and Joyce for school.

Rose glanced at her watch; again the old priest had overslept. She reached into her pocket for her rosary. Good morning, Georgie, she thought, crossing herself. Buongiorno, bello. In the past year, the form of her prayers had changed: instead of asking God for His protection, she now prayed directly to her son. This did not strike her as blasphemous. If God could hear her prayers, it was just as easy to imagine that Georgie heard them, too. He seemed as far away as God; her husband had shown her the islands on the globe. She imagined Georgie’s submarine smaller than a pinprick, an aquatic worm in the fathomless blue.

Stanley had wanted him to enlist. “We owe it to America,” he said, as if throwing Georgie’s life away would make them all more American. Stanley had fought in the last war and returned with all his limbs. He’d forgotten the others—his cousins, Rose’s older brother—who hadn’t been so lucky.

Rose had resisted—quietly at first, then loudly, without restraint. Georgie was a serious young man, a musician. He’d taught himself the clarinet and saxophone; since the age of five he’d played the violin. Besides that, he was delicate: as a child he’d had pneumonia, and later diphtheria. Both times he had nearly died. If America wanted his precious life, then America would have to call him. Rose would not let Stanley hand him over on a plate.

For a time she had her way. Georgie graduated high school and went to work at Baker One. He blew his saxophone in a dance band that played the VFW dances Friday nights. When the draft notice came, Stanley had seemed almost glad. Rose called him a brute, a braggart—willing to risk Georgie’s life so he’d have something to boast about in the beer gardens. At the time she believed it. The next morning she found him gathering eggs in the henhouse, weeping like a baby.

He was strict with the children, with Georgie especially. Only English was to be spoken at home; when Rose lapsed into Italian with her mother or sisters, Stanley glared at her with silent scorn. Yet late at night, once the children were in bed, he tuned the radio to a Polish station from Pittsburgh and listened until it was time for work.

She left the warmth of the church and walked home through a stiff wind, wisps of snow swirling around her ankles, hovering above the sidewalk like steam or spirits. The sky had begun to lighten; the frozen ground was still bare. Good for the miners, loading the night’s coal onto railroad cars; good for the children, who walked two miles each way to school.

At Polish Hill the sidewalk ended. She continued along the rocky path, hugging her coat around her, a fierce wind at her back. Ahead, a group of miners trudged up the hill with their empty dinner buckets, cupping cigarettes in their grimy hands. They joked loudly in Polish and English: deep voices, phlegmy laughter. Like Stanley they’d worked Hoot Owl, midnight to eight; since the war had started the mines never stopped. Rose picked out her neighbor Andy Yurkovich, the bad-tempered father of two-year-old twins. He had a young Hungarian wife; by noon her nerves would be shattered, trying to keep the babies quiet so Andy could sleep.

Rose climbed the stairs to the porch. The house was warm inside; someone had stoked the furnace. She left her shoes at the door. Dorothy sat at the kitchen ta

ble chewing her fingernails. The baby sat calmly in her lap, mouthing a saltine cracker.

“Sorry I’m late. That Polish priest, he need an alarm clock.” Rose reached for the baby. “Did she behave herself?” she asked in Italian.

“She was an angel,” Dorothy answered in English. “Daddy’s home,” she added in a whisper. She reached for her boots and glanced at the mirror that hung beside the door. Her hair looked flattened on one side. An odd rash had appeared on her cheek. She would be nineteen that spring.

“Put on some lipstick,” Rose suggested.

“No time,” Dorothy called over her shoulder.

In the distance the factory whistle blew. Through the kitchen window Rose watched Dorothy hurry down the hill, the hem of her dress peeking beneath her coat. People said they looked alike, and their features—the dark eyes, the full mouth—were indeed similar. In her high school graduation photo, taken the previous spring, Dorothy was as stunning as any movie actress. In actual life she was less attractive. Tall and round-shouldered, with no bosom to speak of; no matter how Rose hemmed them, Dorothy’s skirts dipped an inch lower on the left side. Help existed: corsets, cosmetics, the innocent adornments most girls discovered at puberty and used faithfully until death. Dorothy either didn’t know about them or didn’t care. She still hadn’t mastered the art of setting her hair, a skill other girls seemed to possess intuitively.

She sewed sleeves at the Bakerton Dress Company, a low brick building at the other end of town. Each morning Rose watched the neighborhood women tramp there like a civilian army. A few even wore trousers, their hair tied back with kerchiefs. What precisely they did inside the factory, Rose understood only vaguely. The noise was deafening, Dorothy said; the floor manager made her nervous, watching her every minute. After seven months she still hadn’t made production. Rose worried, said nothing. For an unmarried woman, the factory was the only employer in town. If Dorothy were fired she’d be forced to leave, take the train to New York City and find work as a housemaid or cook. Several girls from the neighborhood had done this—quit school at fourteen to become live-in maids for wealthy Jews. The Jews owned stores and drove cars; they needed Polish-speaking maids to wash their many sets of dishes. A few Bakerton girls had even settled there, found city husbands; but for Dorothy this seemed unlikely. Her Polish was sketchy, thanks to Stanley’s rules. And she was terrified of men. At church, in the street, she would not meet their eyes.

The Condition

The Condition Zenith Man

Zenith Man Baker Towers

Baker Towers News From Heaven

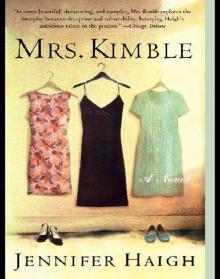

News From Heaven Mrs. Kimble

Mrs. Kimble