- Home

- Jennifer Haigh

Baker Towers Page 2

Baker Towers Read online

Page 2

Rose laid the baby down. Every morning she carried the heavy cradle downstairs to the kitchen, the warmest room in the house. From upstairs came the sounds of an argument, the younger children getting ready for school.

She went into the parlor and stood at the foot of the stairs. “Joyce!” she called. “Sandy!”

Her younger daughter appeared on the stairs, dressed in a skirt and blouse.

“Where’s your brother?”

“He isn’t ready.” Joyce ran a hand through her fine hair, blond like her father’s; she’d inherited the color but not the abundance. “I woke him once but he went back to sleep.”

“Sandy!” Rose called.

He came rumbling down the stairs: shirt unbuttoned, socks in hand, hair sticking in all directions.

“See?” Joyce demanded. She was six years older, a sophomore in high school. “I have a test first period. I can’t wait around all day.”

Sandy sat heavily on the steps and turned his attention to his socks. “I’m not a baby,” he grumbled. “I can walk to school by myself.” He was a good-humored child, not prone to sulking, but he would not take criticism from Joyce. His whole life she had mothered him, praised him, flirted with him. Her scorn was intolerable.

Joyce swiped at his hair, a stubborn cowlick that refused to lie flat. “Well, you’re not going anywhere looking like that.”

He shrugged her hand away.

“Suit yourself,” she said, reddening. “Go to school looking like a bum. Makes no difference to me.”

“You go ahead,” Rose told Joyce. “I take him.” He couldn’t be trusted to walk alone. The last time she’d let him he’d arrived an hour late, having stopped to play with a stray dog.

He followed her into the kitchen. Of all her children he was the most beautiful, with the same pale blue eyes as his father. He had come into the world with a full head of hair, a silvery halo of blond. They’d named him Alexander, for his grandfather; it was Joyce who shortened the name to Sandy. As a toddler, she’d been desperately attached to a doll she’d named after herself; after her brother was born she transferred her affections to Sandy. “My baby!” she’d cry, outraged, when Rose bathed or nursed him. In her mind, Sandy was hers entirely.

Rose scooped the last of the oatmeal into a bowl and poured the boy a cup of coffee. Each morning she made a huge potful, mixed in sugar and cream so that the whole family drank it the same way. In the distance the fire whistle blew, a low whine that rose in pitch, then welled up out of the valley like a mechanical scream.

“What is it?” Sandy asked. “What happened?”

“I don’t know.” Rose stared out the window at the number three tipple rising in the distance. She scanned the horizon for smoke. The whistle could mean any number of disasters: a cave-in, an underground fire. At least once a year a miner was killed in an explosion or injured in a rockfall. Just that summer, a neighbor had lost a leg when an underground roof collapsed. She crossed herself, grateful for the noise in the basement, her husband safe at home. This time at least, he had escaped.

She filled a heavy iron pot with water and placed it on the stove. A basket of laundry sat in the corner, but the dirty linens would have to wait; she always washed Stanley’s miners first. Over the years she’d developed a system. First she took the coveralls outdoors and shook out the loose dirt; then she rinsed them in cold water in the basement sink. When the water ran clean, she scrubbed the coveralls on a washboard with Octagon soap, working in the lather with a stiff brush. Then she carried the clothes upstairs and boiled them on the stove. The process took half an hour, including soak time, and she hadn’t yet started. She was keeping the stove free for Stanley’s breakfast.

“Finish your cereal,” she told Sandy. “I go see about your father.”

She found him lying on the floor, his face half shaven. The cuffs of his trousers were wet. This confused her a moment; then she saw that the sink had overflowed. He had dropped the soap and razor. The drain was blocked with a sliver of soap.

SHE WATCHED THE HEARSE disappear down the hill. A neighbor’s beagle barked. For three days each November it was taken buck hunting. The rest of the year it spent chained in the backyard, waiting.

She had prepared for the wrong death. A month ago, before Christmas, a car had parked in front of the Poblockis’ house to deliver a telegram. Their oldest son was missing, his body—tall, gangly, an overgrown boy’s—lost forever in the waters of the Pacific. Since then Rose had waited, listened for the dreadful sound of a car climbing Polish Hill. Now, finally, the car had come.

In her arms the baby shifted. From the kitchen came a shattering noise.

“Sandy?” she called.

He appeared in the doorway, hands in his pockets.

“What happened?”

He seemed to reflect a moment. “I dropped a glass.”

The baby squirmed. Rose shifted her to the other shoulder.

“Where are they taking Daddy?”

“Uptown. They going to get him ready.” She hesitated, unsure how to explain what she didn’t understand herself and could hardly bear to think of: Stanley’s body stripped and scrubbed, injected with alcohol—with God only knew what—to keep him intact another day or two.

“They clean him up,” she said. “Change his clothes. Mr. Bernardi bring him back tonight.”

The boy stared. “Why?” he asked softly.

“People, they want to see him.” She’d been to other wakes on Polish Hill, miserable affairs where the men drank for hours alongside the body, telling stories, keeping the widow awake all night. In the morning the house reeked of tobacco smoke. The men looked unshaven and unsteady, still half drunk as they carried the casket into church.

Sandy frowned. “What people?”

“The neighbors. People from the church.”

The baby hiccuped. A moment later she let out a scream.

“I go change your sister,” said Rose. “Don’t touch that glass. I be back in a minute.”

Sandy went into the kitchen and stood looking at the jagged glass on the floor. He’d been filling it at the sink when it nearly slipped from his wet hand. A thought had occurred to him. If I broke it, it wouldn’t matter. He turned and threw the glass at the table leg. It smashed loudly on the floor. He had knelt to examine it. It was dull green, one he’d drunk from his whole life. Now, laying in pieces, it had become beautiful, the color deeper along the jagged edges, brilliant and jewel-like. When he reached to touch it, blood had appeared along his finger. Then his mother had called, and he’d jammed his hands in his pockets.

Now he looked down at his trousers. A dark spot in his lap, blood from his finger. He looked at the clock. School had already started; he’d heard the bell ringing as he ran across town for the priest. Tell him to come right away, his mother had said, tears streaming down her face. He’d seen her cry just once before, when Georgie left for the war. Tell him your father is dead.

Sandy straightened. The spot on his trousers was brown, not red as he would have thought. His mother would know he’d touched the glass.

He took his coat from its peg near the door. Joyce would know how to get rid of the spot. He ran out the back door, across the new snow, down the hill to the school.

THEY’D MET STANDING in line at the company store on a summer day. Friday afternoon, miners’ payday: men spending their scrip on tobacco and rolling papers, wives buying sugar and coffee and cheap cuts of meat. Behind the counter, McNeely and his wife filled the orders, writing down each purchase in a black book. Rose’s mother had sent her with a block of fresh butter wrapped in brown paper. Rose churned it herself, to trade each week for cornmeal or sausages or flour for pasta. When her turn came, Mrs. McNeely would weigh the block on a scale. Scarponi, butter, four lbs, she’d write in her book.

Rose held the butter in her apron. Already it had begun to soften in the heat. Behind her two miners waited in line, speaking what sounded like perfect English. The taller man spoke quietly, low and r

esonant. The oak counter beneath her elbow vibrated with his voice. She sensed the closeness of him, his length and breadth; but it was his voice that thrilled her. Even before she turned to look at him, she had fallen in love with his voice.

He’d been a soldier, like all of them. From his size and his blondness she guessed that he was Polish. This explained why she hadn’t seen him before. The Poles had their own church, their parochial school. They were hard workers, serious and quiet. Nothing like the Italian boys, handsome and unreliable; disgraziati who loitered in the town square, sharply dressed, smoking cigarettes and watching the people go by. The Italian boys called after her—after all the girls, she’d noticed: even the plain ones, the heavy, the slow. Rose did not respond. In these boys she saw her uncles, her brothers, her own father, who tended bar at Rizzo’s Tavern and drank most of what he earned. He’d kept his hair and his waistline and his eye for women, while her mother grew hunched and fat, shriller and angrier with each passing year.

Rose looked for the Polish man everywhere: in the street, the stores, the windows of the beer gardens she passed on her way home from work. She lingered at the park where the local team played. Her uncles were crazy for baseball, and that year the Baker Bombers led the coal-company league. On Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays, the ballpark was filled with men.

When she had nearly given up hope, he appeared in the unlikeliest place: the seamstress’s shop where she worked. He was getting married in the fall, he explained. He would need a new suit.

Rose measured his chest, his arms and neck. He did not speak to her, only smiled, bending his knees helpfully so that she could reach his shoulders. Kneeling before him, she took his inseam, then recorded the numbers on a sheet of paper: chest forty-four inches, waist thirty-three. For three weeks she worked on the suit, cutting the fabric, piecing together the jacket and vest. All the while she imagined his wedding, the lovely blond-haired bride—all the Polish girls were blond. Tenderly she assembled the dark wool trousers, the silky inner fabric that would lie against his skin.

The leaves changed color. The suit waited on its hanger. Still the Polish man did not appear. In November, after the American holiday, the seamstress wrote him an angry letter. Finally, on a snowy afternoon just before Christmas, he came.

“Forgive me,” he said, handing the seamstress a check. “I forgot the suit. My plans have changed.” His cheeks were red—from cold or embarrassment, Rose couldn’t tell.

Her fingers shook as she handed him the hanger. He covered her hand with his. That Friday he took her to a Christmas dance at the town hall, and a month later he wore the suit to their wedding. The reception, a raucous affair at his uncle’s house, lasted three days and two nights. For reasons Rose didn’t understand, a pig’s trough had been brought into the house, and Stanley’s older brother had danced a jig in it. Her wedding night was spent in the uncle’s attic. By the end of the festivities she was already pregnant.

She gave birth in the house on Polish Hill, helped by a neighbor woman trained in the old country as a midwife. Stanley considered his own name too Polish, so they called the baby George: the name of the first president, the most American name they knew. Like all company houses, theirs had three upstairs rooms; from the very beginning, the baby had one to himself. To Rose, raised in a cramped apartment above Rizzo’s Tavern, the place seemed cavernous. Her mother had shared an icebox and a clothesline with two other families. The narrow yard had been worn bare by her own chickens and children, and those of the Rizzos and DiNatales.

Dorothy was born a year later, shocking the neighborhood. Nobody had guessed Rose was pregnant; she had gained only a few pounds. For months she’d felt consumed from within and without: the girl baby growing inside her, the boy baby hungry at her breast. Later a neighbor took her aside and explained what all the Polish women knew: secret ways of delaying pregnancy; times in the month to push a man away; special teas that brought on bleeding if a woman was late. The Polish children were nursed for years; in some mysterious way, this delayed the return of a woman’s monthly bleeding. Without such precautions, Rose was told, she’d give birth once a year, until she turned forty or dropped dead from exhaustion. Some women took these methods to extremes. May Poblocki nursed her sons until they started school, for reasons obvious to all: she was a handsome woman, and her husband drank. The women joked that May’s son Teddy, stationed overseas in England, came home on furlough just to nurse.

Rose followed the advice strictly, and her babies came at longer intervals. Three years after Dorothy, she miscarried; the baby dissolved quietly, a soft mass of tissue and blood. Two years later, Joyce was born. Sandy was to be her last child; nursing him, she waited for forty, the age of freedom. Each new baby required time she couldn’t spare, space and money they didn’t have. The mines were slow then; at times Stanley worked only three days a week. In summer the children went barefoot. In winter they lived on dumplings made from stale bread, peppers and tomatoes she’d canned in September. The girls wore petticoats she sewed from flour sacks. Each day after school, Stanley took the older children to pick coal at the tipple; when the shuttle cars were unloaded, there was always some scrap coal that fell by. At suppertime they came back with a wagonload, enough to heat the house for a day.

By her fortieth birthday she had four children—a small family, by the standards of Polish Hill. She and Stanley celebrated her freedom. By then he was working Hoot Owl; each morning he washed up in the basement while she sent the children off to school. Afterward, the house empty and quiet, they climbed the stairs to their bedroom.

She’d been surprised when her cycles stopped. “It’s the change,” said May Poblocki, who’d gone through it herself. The heaviness in her breasts, the strange dreams, the waves of sadness and joy—according to May it was all part of the change. Then, one afternoon as she staked tomatoes in the garden, Rose felt a stirring inside her and knew she was pregnant again.

The baby was born in November, a month after her forty-third birthday. The labor lasted an entire day. Rose scarcely remembered it; later the midwife told her she’d nearly died. Finally Stanley had called the company doctor, who cut her and took the baby with forceps. By then Rose was barely conscious. She remembered light in the distance, the angels coming to get her. When she awoke, the midwife brought her Lucy.

MISS VIOLA PEALE ate lunch at her desk. She disliked the noise of the faculty lounge, its lingering odor of coffee and tobacco smoke. A few of the younger teachers ate in the student lunchroom, a fact Miss Peale found astonishing. Each day she brought the same lunch to school: celery sticks, a tuna sandwich and a boiled egg, prepared each morning by her sister Clara. The prospect of revealing to a pupil the contents of her lunch bag—the distinctive odors of fish and egg—was, to her, unthinkable. It struck her as exposing too much of herself, like coming to school in her slip.

Until that fall she hadn’t so much as sipped a glass of water in the presence of a pupil. Then Joyce Novak asked permission to stay in the classroom during lunch period. She had a chemistry test that afternoon, she said, and she needed a place to study. The boys in the lunchroom made too much noise.

The request took Viola by surprise. Chemistry was a subject few girls studied, one she herself had avoided at the state teachers’ college.

“Please?” said Joyce. She was a fair-haired girl with narrow shoulders and a sharp, birdlike face. The other sophomore girls wore lipstick and tight sweaters—in Viola’s opinion, outfits entirely too sophisticated for girls of fifteen. Next to them Joyce Novak was slender as a child; yet her intelligent gray eyes were oddly adult.

“But what will you eat?” Viola asked.

“I’m not hungry. I’m too nervous to eat.”

“All right,” said Viola. “Just this once.”

Joyce returned to her desk and opened her textbook. Viola reached into her lunch bag and nibbled timidly at her celery. Finally she’d unwrapped her sandwich. The fishy odor seemed especially strong. She wondered if Joyce

noticed.

She ate in silence until the final bell. When it rang, Joyce closed her book. “Thank you, ma’am,” she said politely.

“You’re quite welcome.” Viola had stopped short of peeling her egg, but she had eaten the sandwich and disposed of its wrapping in the dustbin. As far as she could tell, the child hadn’t once looked up from her textbook.

“Joyce,” she said as the girl rose to leave. “I know chemistry is a difficult subject. You’re welcome to spend the lunch period here whenever you need to study.”

Joyce, it turned out, was always studying—chemistry, history, plane geometry. Soon she spent nearly every noon hour in Viola’s classroom. To Viola’s relief, she never asked for help with her lessons. Viola could play the piano; she read and wrote French and commanded a vast mental catalog of memorized poems, but math and science were impenetrable to her. At normal school she’d graduated near the top of her class, but she’d never possessed the acumen she saw in Joyce Novak. She wondered where it came from; in nineteen years of teaching coal miners’ children she had never encountered such an intellect. Often, watching her pupils struggle with Latin declensions or subjunctive tenses, she sensed the worthlessness of what she offered them, the cruelty of teaching geography to children who would never leave Saxon County. And what use was Latin grammar a hundred feet underground?

The Condition

The Condition Zenith Man

Zenith Man Baker Towers

Baker Towers News From Heaven

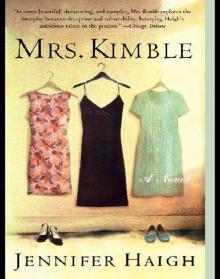

News From Heaven Mrs. Kimble

Mrs. Kimble