- Home

- Jennifer Haigh

Baker Towers Page 6

Baker Towers Read online

Page 6

“That’s not so bad, is it?”

“It feels good,” she admitted.

“Come on.” He led her by the hand toward the center of the pool, until the water reached her chest. Before she realized what was happening, he reached behind her and swung her into his arms.

“Don’t be scared,” he said. “Just lie back. All you have to do is float.”

She exhaled slowly, aware of his arms beneath her. She felt perfectly weightless.

“What about your shoulder?” she asked.

“Don’t worry. I’ve got you.”

She stared up at him: the rough stubble at his throat, the thick scar on his shoulder. Alien textures, hinting at the vast difference between him and her.

“Hang on,” he said. He spun her gently in a circle, his hands gripping her waist, the outside of one thigh. She laughed, delighted.

“Good,” he said. “Now kick.”

She did. A thrill rose in her stomach.

“I could have you swimming in no time,” he said. “You’re a natural.”

Water filled her ears; her heartbeat rose in volume. Dreamily she closed her eyes. The sensation was like nothing she could name; so why did it feel familiar? Heat above her, cold below; herself suspended perfectly between them. His body seemed to be everywhere around her. No man had ever touched her before. Yet that, too, felt familiar.

“Did you hear that?” said Rowsey.

“What?”

“Thunder.”

The lifeguard’s whistle sounded.

“We should get out,” said Rowsey. “Hang on. I’ll float you in.”

A flash of lightning tore across the sky. He drew her in close to his chest.

“Here we are, madam,” he said, releasing her into the shallow water.

Dorothy got to her feet. The pool had emptied out. Patsy was standing at the edge. She wore a terry-cloth romper over her swimsuit. “Where have you been?” she asked sharply.

“Chick was giving me a swimming lesson.”

“The trains are packed,” said Patsy, ignoring her. “We’ll be stuck waiting in the rain.”

He climbed up the ladder, holding his left arm to his side. “Take it easy,” he said, touching Patsy’s shoulder.

“Keep away from me,” said Patsy. “You’re stinking wet.”

They walked to the train station in the rain. Patsy lagged behind; her shoes were giving her blisters. Once, twice, Rowsey stopped so she could catch up.

“For God’s sake, I’m right behind you.”

“Suit yourself.” He fell into step next to Dorothy. “How’d you like your swimming lesson?”

“It was wonderful,” she said, suddenly shy. “Thank you.”

They approached the platform. The crowd was oddly silent.

“What’s going on?” said Rowsey.

“Hush,” said an old woman. “We’re trying to hear.”

Dorothy peered through the crowd. At the center of the platform stood a teenage boy—a redheaded, pockmarked boy with a transistor radio.

“What is it?” said Dorothy. “Did something happen?”

Chick made his way through the crowd. People stepped aside, for reasons that were not clear. His height perhaps, his deep voice, the simple fact of his maleness. He stood a moment, listening intently. Then he called out.

“They did it! They landed in France.”

Afterward she would wonder how it had happened. Had she approached him, or had he come to her? Later this would seem tremendously important; but in that moment there was only his damp shirt, the chlorine smell of his skin, the warm pressure of his mouth on hers. She had seen hundreds of kisses in the movies, but they had not captured the complete feeling: heat, breathing, the movement of another heart. He lifted her high into the air and she was again floating.

Around them the world roared.

IT WAS ALL A MISTAKE.

The Allies had not landed in France. In London, an English girl named Joan Ellis, newly hired as a Teletype operator by the Associated Press, had tapped out the message as a practice exercise: AMERICANS LAND IN FRANCE. Within minutes it was relayed to New York. At the Polo Grounds, where the Giants were up in the third inning, the crowd observed a moment of silence. At the Pentagon, Jean Johns’s old switchboard was besieged with calls.

When the real invasion happened three days later, the celebration wasn’t nearly so grand. Dorothy did not join in the excited chatter at the breakfast table, Mrs. Straub and the deaf schoolteacher and the blond stenographer huddled around the Washington Post. She sat eating the last of her grapefruit, thinking of Chick Rowsey and the day she had nearly learned to swim.

That day, on the streetcar platform at Glen Echo, the pockmarked boy with the radio had shouted in vain; all around him strangers wept and laughed and embraced. Finally he stood on a bench to make himself heard.

“It’s a mistake,” he cried. “They made a mistake.” His eyes tearing, he held the radio close to his ear.

“Quiet!” a young woman cried.

“I can’t hear a thing,” said another, her face streaked with tears.

The voices hushed. Again the crowd gathered around the radio.

“I don’t understand,” said Dorothy. “How do you make a mistake like that?”

When the streetcar came they piled into it, along with the mothers and babies, the girls in straw hats, the wet-haired children and aging grandparents. A lucky few found seats; the rest stood pressed against one another, uncomfortable in their sodden clothes. The rain had stopped, and with it the breeze. Heat rose off their damp bodies, the vinyl seats stuck to damp thighs. No one spoke. Strangers again, they avoided one another’s eyes.

“I can’t believe it,” Dorothy said. She and Patsy sat shoulder to shoulder in the crowded car. Rowsey stood at the other end, smoking.

“Will you stop saying that?” Patsy snapped. “And ask your boyfriend if he can spare a cigarette.”

“He’s not my boyfriend,” said Dorothy, delighting in the words. Even the denial gave her a thrill.

“I know his type,” said Patsy. “He had a good time with you today, but I’ll be surprised if you ever hear from him again.”

Later, at home, she apologized. The heat made her cranky, she said. She was getting the curse.

“I understand,” said Dorothy, her cheeks flushing. Her own periods were unpredictable: sometimes twice in the same month, sometimes three months apart. As a girl, she’d feared bleeding in school, in church, blood running down her leg as she crossed the street. On certain days of the month she could think of nothing else as she sat in class, a fear that paralyzed her when Miss Peale called her to the chalkboard.

The next morning they both had cramps. Patsy complained; Dorothy felt secret relief. She hadn’t bled since coming to Washington. She was shocked and delighted that her body still worked.

For a week nothing happened. In the evenings Dorothy listened to the radio and waited. Another week passed, and she knew that Patsy had been right. She would never see Chick Rowsey again.

Most of these evenings she spent alone. Patsy had a new friend at the CAS, a pretty redhead with a sharp laugh. One Saturday afternoon Dorothy saw them come out of the fitting room at Hecht’s loaded down with dresses. She hid in Housewares until they left the store.

In July a letter came. Her brother Georgie was coming home on furlough. He would spend two weeks in Bakerton, then a final night with Dorothy in Washington before shipping out from Norfolk. Mrs. Straub offered the attic bedroom, a dark little corner outfitted with a narrow cot. “He can have it all to himself,” she said—grandly, as though it were a luxury suite at the Watergate Hotel.

He planned to arrive on a Friday evening. Dorothy would meet his train; afterward they would eat dinner at a restaurant near the station. Already she’d chosen a dress from Patsy’s closet, a dark blue silk she’d admired for weeks. That day she splurged and took the bus home from work. For once there was no line at the bathroom door, and she took her time sett

ing her hair—she’d borrowed Patsy’s foam rollers to smooth out her fuzzy perm. She wrapped herself in a housecoat and headed back to her room. She was surprised to find Patsy there, standing before the armoire in her slip.

“I thought I’d come to the station with you.” Patsy rifled through the closet. “You don’t mind, do you?”

Dorothy hesitated. For weeks she’d imagined showing Georgie around Washington—a city she’d walked end to end, the first place that had ever belonged to her.

“Of course not,” she said. “You’re welcome to come along.”

They dressed in silence. When Patsy picked the navy blue silk off its hanger, Dorothy nearly spoke: I was hoping I could wear that one, if it’s all right with you. Instead she slipped into a dress of her own, a plain green one she’d brought from home. She waited as Patsy arranged her hair and dabbed perfume at her wrists.

Outside it had begun to rain. They stood on the front step, tying scarves over their hair. A gray Plymouth slowed at the curb, flashing its lights. The driver rolled down the window. It was Chick Rowsey.

“Hey, dreamgirls!” He wore a white shirt and a tie.

Dorothy felt flushed, agitated. She remembered the long years of high school, a hundred Friday nights reading magazines, listening to the radio, waiting for something to happen, for her life to begin. Why now? she wanted to say. What took you so long?

“Hey, yourself,” said Patsy. “What are you doing here?”

“Looking for you girls.” He nodded toward Dorothy. “How’s the swimmer?”

“Where did you disappear to?” said Patsy.

“Baltimore. I had to see a doctor up there.”

“We must have missed your phone calls.”

“I’m here now, aren’t I?” He stepped out of the car. “I was hoping you’d be home. I just got my check from Uncle Sam, and I wanted to take you girls out for a steak dinner.” He smiled broadly. “Where are you off to?”

“None of your business,” said Patsy.

“Come on. Don’t be like that.”

Dorothy glanced at her watch. “I’m sorry, Chick, but we really should be going.”

“Where to? I can give you a lift.”

She glanced at the sky, heavy with dark clouds. She felt her hair wilting under the thin scarf. “Union Station. My brother’s coming in on the six-thirty. I’m afraid we’ll miss him.”

“Well, hop in, then.” He opened the passenger door with his good hand. Patsy, sulking, stepped inside. Dorothy followed him around to the driver’s side and got into the backseat.

“This is so nice of you,” Patsy said as he pulled away from the curb. “We’d never have gotten a taxi in this weather.”

“It’s my cousin’s car. I borrowed it special to take you out.” Rowsey glanced over his shoulder at Dorothy. “I’m sorry about dropping off the face of the earth. I want to make it up to you.”

Dorothy hesitated. “My brother ships out in the morning. We have plans for tonight.”

“Just my luck.” He pulled in front of the station. “At least let me wait for you. I’ll drive the three of you back to the boardinghouse. I can’t let a GI walk across town in the rain.”

At the station Rowsey went in search of parking. The girls stared up at the electrified sign that announced arrivals and departures. “We’re late,” said Dorothy, her voice quavering. “We missed him. Now what will we do?”

“There he is!” said Patsy.

Dorothy turned. A man in uniform stood on the platform. She had looked directly at him, but hadn’t recognized him.

“Georgie!” she called, her heart quickening. “Over here!”

He loped toward them, a knapsack over his shoulder. “Hiya, kid,” he said, clasping her briefly. Except for the day he’d left for boot camp, he had never embraced her before. He was taller than she remembered, bigger through the shoulders. His dark hair had thinned at the temples; his face looked long and thin. He reminded her of their father.

“I can’t believe it’s you,” she whispered.

He let go first.

“Who’s this?” he asked, grinning.

“Patsy Sturgis.” She gave him a dazzling smile. “I recognized you right away.”

“How’s that?”

“I wake up every morning looking at you.” She giggled at his expression. “Dottie keeps a photo of you on the bureau.”

“Patsy’s my roommate,” Dorothy explained.

“No kidding.” His eyes rested on her a moment.

“Hey!” Rowsey called from across the platform.

Patsy ignored him. “How was your train ride, George?”

“No complaints.” He glanced at Rowsey, who was hurrying toward them. “That guy a friend of yours?”

“That’s Chick Rowsey. He drove us here.”

“Are you hungry?” Patsy asked.

“There’s a place nearby that makes great hamburgers.” Dorothy had never eaten there herself, but Jean Johns had once gone there on a date.

“You mean Morrison’s? That’s pretty tame for a returning hero.” Patsy cocked her head at Rowsey. “Hey, big spender. Didn’t you say something about steaks?”

He grinned sheepishly. “It’s Friday night. A table for four might be tough to swing.”

“I’m sure you can do it.” Patsy turned to Georgie. “When’s the last time you had a Delmonico steak?”

“A long time,” he admitted, grinning. “A coon’s age.”

“Then it’s settled.” Patsy took his arm. “We’re going to Patrick Henry’s.”

THEY CROWDED into a booth near the kitchen, a cozy semicircular one meant for a couple. Georgie sat in the middle, the girls on either side. A waiter brought an extra chair for Rowsey. Drinks were ordered: beers for the men, Coca-Colas for the girls. When the waiter disappeared, Rowsey produced a flask from his pocket. He took a swig and handed the bottle to Georgie.

“What is it?” said Patsy.

Rowsey grinned. “It’s not suitable for ladies.”

“That’s not fair,” she said. “It’s rude not to share.”

Rowsey clapped Georgie’s shoulder. “Two weeks’ leave, huh? How’d that happen?”

“Don’t ask me, pal. How does anything happen?”

Patsy leaned forward. “Dorothy says you have a girl back home. Evelyn, isn’t that right?”

Georgie shot Dorothy a look. “Not anymore. That’s finished now.”

“What do you mean?” said Dorothy.

“Ev’s marrying Gene Stusick.”

“Gene? I can’t believe it!” Their fathers had worked on the same crew. From school, from church, the six Stusick children were as familiar as cousins. “You two were always such good friends.”

“It’s no big deal.” Georgie drained his glass. “I don’t mind. I wish them the best.”

“Women,” said Chick. “You can’t count on them.”

Georgie lit a cigarette.

“You smoke now?” said Dorothy.

“Off and on.” He grinned. “I haven’t had one all week. Not with Mama around. It wouldn’t have been worth the grief.”

“All GIs smoke,” said Patsy, reaching for his pack. “Isn’t that so?”

“Most of them. But it’s a bad habit.” George nudged her. “Especially for a girl.”

“It’s worse for a girl,” Rowsey agreed solemnly. “Makes her look fast.”

Patsy giggled. “Watch it, buster.”

“You’re a bad influence,” said Georgie. “You didn’t get my sister started, did you?”

“Not Dorothy,” said Rowsey. “She’s not that kind of girl.”

Dorothy felt a flush creep across her cheeks. The conversation embarrassed her, but it was delightful to be out with her brother. He was glad to see her; he looked handsome in his uniform. They had not laughed together in years.

Rowsey raised his glass. “They say it’s almost over.”

“They said that a year ago,” Georgie said.

THE CAR WOUND slowly thr

ough the dark streets. Dorothy sat up front next to Rowsey, Georgie and Patsy in the rear. The rain had stopped. A dense fog blanketed the warm night. Dorothy’s watch showed two-thirty. She’d never seen Washington at this hour. She was surprised by how much activity there was.

They stopped at a light on Sixteenth Street. At the corner two men stood smoking cigarettes. Across the street, a soldier and his girl leaned against a low wall, kissing.

“Lively neighborhood,” Georgie observed.

“There’s an officers’ club up ahead,” said Rowsey.

In the backseat Patsy murmured something to Georgie, and he answered in a low voice. She giggled shrilly. Dorothy glanced in the rearview mirror, wondering what was funny.

Rowsey turned onto Massachusetts Avenue and stopped in front of the boardinghouse. The engine idled loudly in the quiet street. In an upstairs window a light came on.

Patsy stepped out of the car, adjusting her skirt. “Good Lord, I’m tired.”

“Rowsey,” said Georgie, hefting his duffel to his shoulder. “Good to meet you, pal.”

“Good night,” Dorothy added, but Rowsey seemed not to hear her. He shook Georgie’s hand.

“Aren’t you coming?” Dorothy called from the stoop. Patsy had re-seated herself in the car.

“In a minute.” She tucked her legs up under her. “Go ahead. I’m right behind you.”

Dorothy led Georgie up the steps. Her heels clicked loudly on the cement.

“What’s the story with those two? She seems mad at him about something.” Georgie glanced toward the car. Rowsey had cut the engine; he and Patsy seemed deep in conversation.

“She’s always mad about something,” said Dorothy.

“She’s a funny girl.”

Dorothy unlocked the door. His curiosity irritated her, mainly because she knew Patsy would interrogate her later: What did your brother say about me? Patsy, who already had two fellows overseas, who at that very minute was sitting in Chick Rowsey’s front seat. It occurred to her that Patsy wouldn’t be satisfied until every boy in the world was thinking about her.

She led Georgie to the attic room and switched on the light, a single bare bulb hanging from the ceiling. A cot had been made up with sheets and a blanket. “I hope it’s not too uncomfortable.”

The Condition

The Condition Zenith Man

Zenith Man Baker Towers

Baker Towers News From Heaven

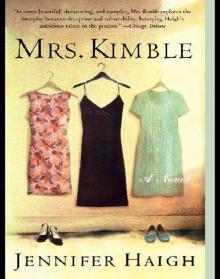

News From Heaven Mrs. Kimble

Mrs. Kimble